The Story of Beaumont

Spindletop, the Wonder Oil Field

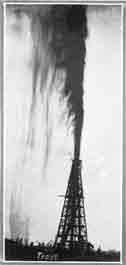

Lucas Gusher

(click here for larger image)

FROM the brain of a poor boy -- a dreamer, they called him -- came Spindletop, the wonder oil field of history.

Back in the sixties there were sour wells on Spindletop and the waters were said to be of great medicinal value. Several shallow wells walled with boards were sunk, practically all of them producing a different water, both in taste and mineral composition. The miniature health resort was abandoned during the war, but the story of the wells was well known.

Patillo Higgins, a poor Beaumont boy, looked beyond the shallow bottoms of the wells.

With the limited books at his command, he began the study of geology. He came to the conclusion that petroleum and gas were responsible for the water produced in the wells. The tiny bubbles coming up on the surface of the water like the patter of rain on a still pond, convinced him that there was a great gas pressure somewhere far below the surface of the earth.

Once convinced, he set about to organize a company for the purpose of testing out his theory. This was realized largely through the financial assistance of the late Captain George W. O'Brien and George W. Carroll. The Gladys City Oil, Gas and Manufacturing company was organized in the early 90's. The company was named after Miss Gladys Bingham, now Mrs. J. Bain Price.

An attempt was made to sink a well in 1894, but the driller failed to get down. The same discouraging results were experienced in 1896 and 1898. But Mr. Higgins never faltered in his efforts, never lost faith in his judgment, and passed by the scoffing of the skeptical without comment. Without his faith and consistency, the opening up of Spindletop and other enormous petroleum deposits in Texas, Louisiana, Arkansas, Oklahoma and Kansas might have been delayed many years. The discovery of Spindletop made Beaumont the best advertised town of its size in the world, and caused it to rapidly grow into a modern city. In the mining and industrial world, Patillo Higgins occupies a position along with Daniel Boon, Kit Carson, Lewis and Clark, and other great pioneers who carved paths for civilization through the trackless forests, mountains and plains of the west.

Through Spindletop Beaumont has the distinction of opening up the greatest mining era in the history of the New World. The gold discoveries of California in 1849, the later development at Cripple Creek, Colorado, and Alaska, pale into insignificance when compared to the millions that were extracted from the earth following the discovery of the Lucas Gusher on Spindletop in January, 1901.

Only in far-away Russia had such monster gushers been discovered before. But Russia was far removed from the great industrial centers, and the Baku fields had no marked effect upon oil as a fuel. None of the railroads in the United States had thought of oil as fuel, neither did the steamships use it. Coal. was still the dominating steam producer of the civilized world.

The Spindletop discovery was cabled across the Atlantic and attracted attention of oil men and scientists in all parts of the world. Skepticism was rampant, not over the production which was estimated at 70,000 barrels a day, but the set belief that it was a freak that would soon exhaust itself -- probably a crevice, and no other wells could be struck.

The Lucas gusher came in with a roar, blowing the drill pipe out of the hole, and ran wild for ten days. A great lake of oil was formed before it could be brought under control, Rocks highly impregnated with sulphur, tore the top of the derrick into shreds as if it had been between opposing armies.

Thousands of oil men gathered in Beaumont while the well was flowing, and thousands of acres were either bought or leased. Again there was a pause, until scores of other drills, working day and night, might tell their own tale. In April of the same year the Beatty gusher was brought in, several hundred feet from the discovery well and the remainder of the story is one of hope, wealth, and despair. Men came to Beaumont penniless and went away millionaires. Others came here wealthy and left penniless. It was a game men played to their last dollar, and they hardly slept until the results were known. Hundreds of small companies were organized, and in nearly every village and hamlet in the United States owners of Beaumont oil stock could be found.

Oil lands rapidly grew in value, but an effort was made to make room for all of them on Spindletop. Many acres were divided up into 1-64ths, which gave room enough to drill a gusher. One concern made it a business to contract with a newly-organized company to bring in a six-inch gusher for the nominal sum of $25,000. Anywhere the drill went down on Spindletop proper a gusher was the result. One woman who collected garbage in Beaumont daily sold her pig pasture for $35,000.

The failure of so many companies was due entirely to the lack of a market. Thousands of barrels of oil were contracted for and delivered at 3 cents a barrel, and in some instances for 2 cents a barrel. There were no pipe lines, and only a limited number of tank ships and tank cars. Railroads had not yet started using oil for fuel, and it was unknown in the ships on the high seas.

It was then argued that the oil was too heavy for refining purposes, but this theory was soon exploded. Within a short time tankers began to carry it out to refineries along the North Atlantic and in Europe. More pipe lines were conducted, and the work of building refineries in Jefferson county began. Today Jefferson county is the largest oil-refining district in the world, turning out more wealth annually than the miners of California ever dreamed of.

Railroads and industries began to use crude oil for fuel, and then it was tried out in ships. Today most of the navies of the civilized world use oil for fuel, and it is burned under the boilers in thousands of commercial ships and most of the locomotives. Refineries in and around Beaumont forwarded most of the lubricants and fuel used by the allied navies during the World War and the gasoline that drove the trucks on the battlefields of France and Belgium.

Spindletop furnished an incentive for the prospectors to search for other fields. These wildcatters, as they are known in oil circles, spread out in fanlike shape, opening up Sour Lake, Saratoga, Humble, Batson and Jennings. On they swept to North Louisiana, Oklahoma, and then Kansas, and finally north Texas and Arkansas. The wave of liquid gold swept hundred of miles north, east and west, with Beaumont remaining the basis of the industry. Pipe lines followed the wildcatters as the reported success, and the lines that first reached from Beaumont to deep water turned northward and crept through forests, over hills and across the prairies of Oklahoma and Kansas to bring the fluid to the discovery point.

Today these pipe lines converging in Beaumont and spreading out like monster talons from north Texas on the west to Arkansas on the east and north to Kansas, represent investments of hundreds of millions of dollars, while the value of oil properties represented in producing wells, refineries, pipe lines, pumping stations, storage tanks, and other equipment following the discovery of oil at Beaumont, pass far beyond the billion-dollar mark.

The mother of the great oil development area is still producing oil, although it has settled down to something around one thousand barrels a day. Although the enormous gas pressure formerly rushed it out through six-inch casing up to 212 feet in the air, this being recorded in Heywood No. 4, no power could rob the rich deposits so quickly and it still trickles through the sand and honeycombed rocks that formerly produced the gushers. Walking beams still are nodding away like some sleepy giant, and bringing to the earth the greatest known agency in modern civilization -- oil.

This chapter was written from first-hand information by Robert S. Waite, a resident of Beaumont at the time oil was discovered. Acknowledgment is due Mr. Waite also for other aid in the preparation of this volume and for the use of his files containing information about Beaumont.