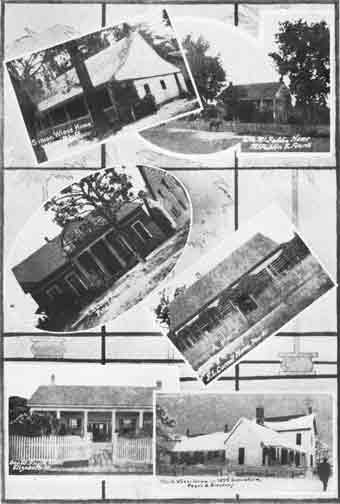

The Story of Beaumont

Homes of Early Days

THE history of a people is told by its houses and by its household goods, The day of the prairie schooner and the westward migration, of the log cabin and the struggling settlement, of new importations, and modern success, each of these phases in the development of the section has had its silent representative in the architecture of Beaumont homes.

How well Beaumont pioneers built for future generations is shown in some of the houses erected almost a century ago that are still being used by descendants of those same pioneers. Such a home is that of Mrs. Pauline Wiess Coffin at Wiess Bluff on the Neches river, built in the fall of 1858 by her father, Simon Wiess, and a description of that residence is an accurate picture of the early homes of the Beaumont settlers.

The house is situated on a bluff overlooking the Neches on two sides, with a porch 75 feet long, extending its length. A bannister railing is attached by hooks to the gallery, so that it may be let down and used as a shelf for airing mattresses, blankets and quilts. At one end and entirely separate except for a covered passage, are the dining room and kitchen.

Show Places of Pioneer Beaumont

(click here to see a larger image)

The house has six large rooms, built on either side of a great hall, in addition to kitchen, dining room and two store rooms. A den flanked with stuffed animals that were killed at the Bluff is an interesting feature; then, too, there is the old wooden bucket with cover and gourd, that is kept filled with water from one of the three cisterns on the place that contains cooler water than the others.

Old-fashioned heavy beds, with testers, marbletopped tables, a grandfather's clock, walnut highboys, tall glass candle shades to keep the wind from blowing out the lights, are some of the prize possessions of this home.

The flower garden, quaint and orderly, has been retained practically as it was originally planned. All the walks are bordered by yellow stone quart bottles that came from abroad, and massive liveoak trees shade the yard. Pink crepe myrtle, red roses, gladioli and bachelor button flaunt their loveliness in the old-fashioned garden that radiates an air of romance of bygone days.

A builder's contract of the early period will also give an idea of the type, size and cost of houses in that day. Such a contract made between William E. Hatton and William Stephenson on April 29, 1841, specifies that Hatton is to build a house of the following dimensions, to wit, a frame one and one-half story high, 18 feet wide and 26 feet long with galleries, 10 feet wide on two sides; and the price of Hatton's work, including his furnishing 700 feet of plank, is $550. Hewn cypress timber was to be used in the construction of the home, with cypress shingles for roofing, and four doors with batten shutters, nine windows with five having batten shutters were to be put in.

By far the greater number of the dwelling houses of this period of Beaumont's history, however, were log houses chinked with mud, and practically all consisted of two large rooms erected on either side of a wide hall left open at the ends, so that the Gulf breeze could sweep through, with a mud chimney built to accommodate eight to ten foot log heaps. One early settler, Mrs. R. N. Weber, recalls seeing cattle break and run through the open hallway of the home of young Noah Tevis, located about where Pipkin park now is, while the family was entertaining guests.

The material for the log houses cost little or nothing except the labor in cutting and preparing the timbers. "Log raisings" were very popular in those days, and it, was only a matter of a few hours with the two teams racing against each other, to heave the logs in place, chink the crevices with mud, and have the house completed with the exception of the chimney and the roof. The latter was made from cypress split shingles, and a swarming crew soon finished it.

Then came the sport of chimney daubing. Four poles as long as the chimney was to be high, were set upright where the four corners of the completed chimney would come. Holes were drilled every three or four inches in these poles, allowing numerous cross sticks to be inserted, joining all of the poles together and having the appearance of rungs in a ladder. When the chimney frame was completed the "mud cat" was introduced.

The "mud cat" was a composite mass of grey moss and mud, about two inches thick, four to six inches wide, and as long as the distance between the upright poles. The moss was in the center with a thick coating of mud. As each man finished a "mud cat" he heaved it to the man on the chimney. The "cats" were hung across the horizontal sticks, half on either side. Beginning on the bottom rung, each "cat" overlapped the one immediately below it. They were then plastered with mud, inside and out, to prevent the moss from igniting after the heat of the fire had dried it out.

Now most of the old houses are gone. Few traces are left. Where they stood so bravely, landmarks for travelers by land and water, gigantic steel skeletons tower toward the sky, and modern mansions of stone and brick, the homes of the descendants of those hardy pioneers, line the same streets where once stood their modest homes. Like those who lived and loved and moved within their walls, the old homes are gone.